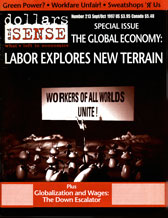

Globalization and Wages

The Down Escalator

This article is from the September/October 1997 issue of Dollars and Sense: The Magazine of Economic Justice available at http://www.dollarsandsense.org

This article is from the September/October 1997 issue of Dollars & Sense magazine.

Real wages for most Americans have been falling for more than two decades. But what is the culprit? Is it the decimation of unions? The falling value of the minimum wage and the loosening of regulations meant to protect workers? Technology, by raising the demand for highly-skilled workers while the need for those with lesser skills falls? Or is it international competition, by destroying high-paying factory jobs and driving wages toward third-world levels?

While the answer may be all of these, how much responsibility each factor deserves is hotly debated among economists, politicians, and activists—and opinions are not divided along the usual left-right spectrum.

With industrial jobs shrinking in the United States, and so much of what we buy, from clothing to electronics to automobiles, now made abroad, a common perception is that "globalized" production is a primary cause of falling living standards for American workers. But most economists, including some progressives, believe that this perception is misdirected and alarmist.

They argue that the activities of multinational corporations (multinationals) are still concentrated in the wealthy "Triad" (North America, Europe, Japan) rather than in low-wage countries. As a result, contend economists like MIT's Paul Krugman and his more conservative colleague and Business Week columnist Rudy Dornbusch, trade between rich countries and poor is not large enough to affect the welfare of most workers in the Triad.

Some on the left add that globalization, even if real, poses less of a threat to workers than corporate downsizing, union busting, deregulation, and technological changes. Left Business Observer editor Doug Henwood reminds us, for example, that massive numbers of high-wage jobs in the trucking and airline industries were converted into low-wage ones as a result of deregulation, without the involvement of any third-world labor.

But while these other factors are important, it would be wrong to minimize globalization. International trade and production are major factors in the world economy, and not only in manufacturing industries where imports are large. Their effects ripple through national economies like ours, depressing wages, increasing inequality, and strengthening the bargaining power of capital relative to labor.

Labor in the Cross-Hairs of Capital

NAFTA AS HERO OR VILLAIN?

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) among Canada, Mexico, and the United States has now been in effect for three years. Globalization advocates, including Bill Clinton, have heralded it as a major step forward for all involved, while the conservative Heritage Foundation says that under NAFTA "trade has increased, U.S. exports and employment levels have risen significantly, and the average living standards of American workers have improved."

Yet the evidence shows the opposite. First, recent research by Kate Bronfenbrenner of Cornell University confirms that globalization shifts bargaining power toward employers and against U.S. workers. Bronfenbrenner found that since the signing of NAFTA more than half of employers faced with union organizing and contract drives have threatened to close their plants in response. And 15% of firms involved in union bargaining have actually closed part or all of their plants—three times the rate during the late 1980s.

Second, NAFTA has caused large U.S. job losses, despite claims by the White House that the United States has gained 90,000 to 160,000 jobs due to trade with Mexico, and by the U.S. Trade Representative that U.S. jobs have risen by 311,000 due to greater trade with Mexico and Canada. The liberal Economic Policy Institute (EPI) points out that the Clinton administration looks only at the effects of exports by the United States, while ignoring increased imports coming from our neighbors. EPI estimates that the U.S. economy has lost 420,000 jobs since 1993 due to worsening trade balances with Mexico and Canada.

Research on individual companies yields similar evidence of large job losses. In 1993 the National Association of Manufacturers released anecdotes from more than 250 companies who claimed that they would create jobs in the United States if NAFTA passed. Public Citizen's Global Trade Watch surveyed 83 of these same companies this year. Trade Watch found that 60 had broken their earlier promises to create jobs or expand U.S. exports, while seven had kept them and 16 were unable or unwilling to provide data.

Among the promise-breakers were Allied Signal, General Electric, Mattel, Proctor and Gamble, Whirlpool, and Xerox, all of whom have laid off workers due to NAFTA (as certified by the Department of Labor's NAFTA Trade Adjustment Assistance program). GE, for example, testified in 1993 that sales to Mexico "could support 10,000 [U.S.] jobs for General Electric and its suppliers," but in 1997 could demonstrate no job gains due to NAFTA.

—Marc Breslow

To see why, let's review recent trends in global trade. At a swift pace in recent decades, barriers to international trade, investment, and production have fallen. Transport and telecommunications have become much cheaper and faster, greatly improving the ability of multinationals to manage globally dispersed activities. Tariff and nontariff barriers have been removed through international agreements, including NAFTA, the European Union, and the World Trade Organization, while the proposed Multilateral Agreement on Investment is looming.

Since the 1970s trade in goods and services has been increasing much faster than world output, the opposite of what happened in the 1950s and 1960s. From 1970 through the mid-1990s, world output grew at a rate of 3% per year, trade volume at 5.7% per year.

For the United States, the ratio of exports and imports to gross domestic product (GDP) changed little over most of the present century, but from 1972 through 1995 it rose from 11% to 24%. By 1990, 36% of U.S. imports came from developing countries compared with 14% in 1970. For the European Union, imports from developing nations grew from 5% to 12% over the same period (the proportions would have been much higher if trade between European nations was excluded, just as interstate trade is excluded from U.S. foreign trade figures).

Multinationals' use of developing nations for production is substantial and growing, especially in Latin America and Asia (excluding Japan). By 1994 it accounted for a third of all trade between U.S. multinational parents and their affiliates, and at least 40% of their worldwide employment (seven million in 1994).

Yet most trade economists, including Paul Krugman, William Cline and Robert Lawrence, deny that global forces have much to do with exploding wage inequality. International trade, they maintain, takes place largely on the basis of "comparative advantage": countries gain from exporting goods that they are relatively most efficient at producing, while importing goods that they are relatively less efficient at producing. By this logic, the United States would specialize in exporting goods that require large amounts of skilled labor and hi-tech equipment; it would import goods embodying relatively large amounts of unskilled labor, mainly from developing countries.

Free trade benefits all countries, this theory assures us. In 1996, for example, President Clinton's Council of Economic Advisers reported that in a sample of 79 nations, those with "open" economies (relatively unrestricted trade rules) enjoyed a much faster rate of GDP growth over the past 20 years than those with "closed" economies.

"Comparative advantage" theory does admit that some groups will benefit at the expense of others. For the United States, the demand for high-skilled labor and owners of high-tech equipment will increase while demand for less-skilled labor will fall. This, in turn, will raise the wages of the high-skilled and the profits of the owners, while lowering the wages of less-skilled workers. The result: greater inequality.

But most mainstream economists insist that these effects should be small. Trade, they point out, hits only specific industries, not the entire economy. And while trade between developed and less developed countries may be growing, manufactured imports from those nations still represent only 2% of the GDP of developed countries. For most of the Triad, the bulk of economic activity is domestic, and trade takes place largely among developed economies where wages and working conditions are similar.

Many trade theorists also deny that U.S. producers will transfer skilled jobs to developing countries to cut wage costs. This tactic will fail in the long run, they argue, because the productivity of foreign workers would rise toward U.S. levels, and wage increases would soon follow. "If a Mexican worker's output goes from one widget to 10 widgets a day, his wage rises to that level," according to Krugman. "This is the only explanation that makes sense."

Such arguments lead to one conclusion: international trade might cause some rise in inequality, but not the dramatic widening of the earnings gap between highly skilled labor and nearly everyone else that has developed since the 1970s. To explain this gap, economists have a favorite culprit—technological innovation that cuts demand for low-skilled workers and raises demand for the high-skilled. The problem is not globalization, the argument goes, but widespread adoption of computer-based technologies, creating a "skill mismatch" that blocks the way to good jobs for lesser-skilled people.

But this runs into a problem: technology may be responsible for part of the wage gap between the highly educated and the less-skilled, but it cannot explain the severe drop in real wages for most U.S. workers. Why not? Because the evidence for higher skill requirements is unclear. Peter Capelli of the Wharton Business School found, for instance, that skill requirements have risen in some jobs, while other jobs were eliminated due to automation. But New School economist David Howell's research indicates that the skill demands of most occupations have changed little since the 1970s. The new technologies actually reduce some skill requirements, and increase job opportunities for the low-skilled; the use of scanners by cashiers is one important example.

Other Economists Say... "Oh, Yes it Can"

For some economists, the link between globalization and wage inequality is far stronger. Adrian Wood of the University of Sussex (U.K.) argues, first, that less developed countries now export the same manufactured goods that have been produced in Triad countries (toys and cameras, for example), but they use much greater amounts of low-skilled labor. Not only would more low-skilled American workers have been needed had these goods still been produced in the United States; those workers would have been paid at higher wage rates as well.

Second, Wood observes that to fight off imports from developing countries, U.S. and other Triad firms are forced into "defensive innovation"—changing technology in ways that further reduce their demand for unskilled labor. So at least some of the technological innovations that trade economists contend are more important than trade in explaining inequality may themselves result from that trade.

These two developments lead Wood to conclude that expansion of trade with developing countries is "the main cause of the deteriorating situation of unskilled workers in developed countries." In this judgment Wood is not alone. R.C. Feenstra and G.H. Hanson find that outsourcing accounts for 30% to 50% of the decrease in unskilled labor's share of U.S. wage income between 1979 and 1990.

The Many Ways That Corporations Trade

Intrafirm trade, or cross-border transactions between units of multinational corporations, has been expanding since the 1970s. It comprises exports from parent companies to their foreign affiliates, affiliates to parents, and affiliates to affiliates. The largest channel for U.S. multinationals in 1993, and the most rapidly growing one, was the third, trade among affiliates outside the United States, accounting for 44% of total intrafirm trade of $380 billion. Much of this three-way trade consists of materials and components for further processing or assembly; the rest includes near-finished goods for wholesale trade and finished goods for sale to consumers. Data for multinationals based in Japan, France, and Sweden confirm the importance of intrafirm trade channels in geographic dispersion of production activities.

Yet intrafirm trade figures understate the effects of "outsourcing," which includes not only intrafirm exports from affiliates back to parents, but also goods produced by independent subcontractors to be used in further production by the parent firm or sold under its brand name. Including such subcontracting, outsourcing "has expanded dramatically over the last two decades," say economists Robert Feenstra and Gordon Hanson. Between 1972 and 1990 imported intermediate inputs of all types increased from 5% of total material purchases by U.S. manufacturers to 12%. These figures in turn hide a much higher propensity to outsource in certain industries—textiles and apparel, footwear, consumer electronics, instruments, toys, sports equipment, and others. Involved are multinationals like Nike, K-Mart, Compaq Computer, and General Electric, which imports all the microwaves sold under its own name from Samsung in Korea.

—Richard Du Boff

Gary Burtless of the Brookings Institution and Edward Leamer of UCLA are wary of these estimates, but they agree that trade is a major culprit. They refer to intensified pressures on Triad-based firms to match wages for workers in the rest of the world. As long as there are some unskilled workers in the United States producing the same items as workers in China, Leamer argues, U.S. wages will be driven toward Chinese levels. And rather than affecting only low-skill, export-good industries, "what an unskilled worker gets paid in our traded good industries is going to automatically flow through and influence the wage paid to unskilled workers in all U.S. industries," Burtless observes.

As international trade wipes out jobs in manufacturing, the displaced workers seek jobs somewhere in the service sector, exerting downward pressure on the wages of maintenance and custodial workers, taxi drivers, fast food cooks, and others who hold similar positions. Even if the displaced workers can be absorbed easily, their new service jobs will usually pay less than their old jobs, pulling down average low-skill wages.

And the effects will not be restricted to low-skilled labor. A worldwide labor supply network is now extending to middle-range skills. India has a large pool of English-speaking engineers and technicians who make roughly the same wages as low-skilled workers in the United States. A $100,000 a year computer circuit board designer in California will cost less than a third as much in India. The Philippines, the Caribbean, and Ireland each have many thousands of workers with more than basic educations, who are available for everything from customer account servicing to data processing. The result is access by Triad producers to a viable, low-cost source of skilled people, who can be instantaneously integrated into production schedules via satellite, the costs of which have dropped 90% since the 1970s.

The effects on all but the most highly skilled workers in the Triad are intensified by the speed with which technologies and managerial practices can be moved around the world. The most striking illustration may be Mexican automobile facilities, which are on a par with those in Japan and the United States and hire workers educated in Mexico's public universities, technical institutes, and secondary schools. Some of these graduates are already "overqualified for the jobs they now can get," says the director of Chihuahua's Institute of Technology. These workers are paid about one-eighth of what their U.S. counterparts get, even though quality and productivity sometimes exceed U.S. levels.

According to GM's own criteria, most of its top-rated factories are in Mexico, and in its Sao Paulo (Brazil) plant GM has been able to gear up production of a new sedan in half the time it took a GM factory in Kansas to do the same just last year. Similarly, Hewlett-Packard's Singapore facility has been designated as its global R&D and production center for portable printers. "Again and again in my visits to factories in Mexico and Southeast Asia," reports Harvard Business School's Robert Hayes, "I have been struck by their enthusiastic adoption of the most advanced approaches to production management."

Harvard's Dani Rodrik focuses on how globalized trade and investment not only allow employers to reduce their need for low-skilled labor in the Triad, but also make companies more likely to jettison workers when wages rise even modestly. Small wage increases may cause large-scale layoffs, if producers can switch to lower-wage options abroad.

The result, notes Rodrik, is that workers have less bargaining power. The global spread of production makes it harder for unions and workers in the developed world to defend their relatively high wages and good working conditions against the credible threat to close up shop and shift production of goods elsewhere. Mainstream economists generally ignore bargaining power as an issue; Krugman's assumption that Mexican "widget" workers would be able to push up their wages to match any productivity gains is a perfect example.

Meanwhile, back on planet Earth, the mere threat by multinational managers to relocate production abroad may be sufficient to wring wage concessions from their workers, who will nonetheless remain vulnerable to escalated threats in the future. "Demonstration effects" like this have always been a weapon of choice for capital in its confrontations with labor.

Less bargaining power for workers means greater vulnerability for progressive public policies, including mainstays of the welfare state—unemployment compensation, disability benefits, pensions, and medical care. In short, the heightened ability of capital to shed workers and cut the social wage underlies the "race to the bottom" that progressive economists have prophesied and mainstreamers have pooh-poohed.

Together, manufacturing imports from the developing world, outsourcing, and transfers of production technologies abroad undermine wage structures in the Triad. The connection between globalization and income inequality is anything but coincidence. For Rodrik, it is a major reason "why life has become more precarious, and insecurity greater, for vast segments of the working population."