Where the Climate Buck Stops

Climate superfunds are a sensible way to put some of the costs back where they belong, but we’ll get them only if the public demands them.

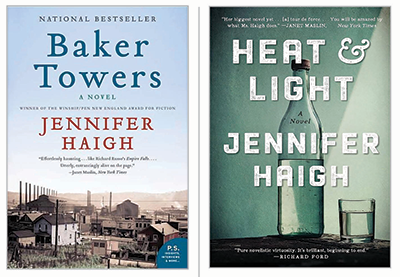

In two novels published 11 years apart, Jennifer Haigh conjures the history of a fictional but utterly plausible Pennsylvania coal town called Bakerton. (There is also a collection of short stories set in Bakerton published in between the novels.) Within the first few pages of Baker Towers (2005), we learn, “The mines were not named for Bakerton; Bakerton was named for the mines. This is an important distinction. It explains the order of things.” The mines were named for the Baker brothers, wealthy men who saw an opportunity to expand their wealth and power by investing in coal mining and governing the town that sprang up to house its workforce. This first novel in the set begins with the sudden and premature death of coal miner and father of five Stanley Novak in 1944 and follows the lives of his widow and children, and by extension the whole social world of Bakerton, up to the 1970s, when the mines close.

The main story of Heat and Light (2016) begins decades later, in the 2010s. One centenarian, Ada Thibodeaux, can recall her grandmother’s recollections of Colonel Drake’s arrival and his interest in what the locals called “rock oil” and couldn’t find a use for. The oil drilling called forth towns: “Pithole, Petroleum Center, and Antwerp City—names the old-timers have forgotten and the young never learned, ghost towns that boomed once, when a well came in, then busted and stayed busted the rest of their days.” Bakerton in the 2010s is not as ghostly as those defunct oil towns, but without the coal mines, the economic foundations of residents’ lives are shaky. The anchor institutions now include the hospital and the nursing home, where ex-miners who have not yet died of black lung are treated and housed, and the prison, which locks up a handful of local small-town miscreants but mostly mines the big city miseries of Philadelphia and Pittsburgh’s underclasses. The core ensemble of characters includes Rich Devlin, who used to drive a truck delivering oxygen tanks to former miners. When the prison opened, he got work as a guard, which he finds better paid and marginally less depressing. Rena Koval is a nurse at the hospital. Rounding out the economic picture of the place, there are a handful of small farms and the less legal, highly disruptive activity of cooking meth. (Fertilizer stolen from the farms is an ingredient in the meth recipe.) Now energy companies investing in natural gas have their eyes on the Marcellus Shale, over which the Bakerton residents live. “More than most places,” Haigh observes, “Pennsylvania is what lies beneath.”

The relationships between Bakerton’s residents and the fossil fuels embedded in the ground, and between Bakerton’s residents and the flows of capital that direct the extraction of the fuels, have the feel of Greek tragedy. The accumulation of carbon deposits at the timescale of geology, the accumulation of capital at the timescale of corporate quarterly reports (or even minute-by-minute movements of the stock market)—all of it feels like the workings of fate, the effects on ordinary, human-scaled lives no more alterable than the careless spillover effects of feuds among gods in ancient myths and dramas.

The relationships also have an element of romance. The relationship of Bakerton to coal, especially, though it is not an idyll, is a love story. “Bakerton Coal Lights the World.” It is a public relations slogan. Everyone knows that, just as they know that the mines kill the community’s men. The demographics of the guests gathered at a party hosted by Gene and Evelyn Stusick illustrate the toll:

Adults crowded the living room—young couples, old women. Past a certain age the men seemed to disappear. The lucky ones, like Gene’s uncles, hobbled around on canes, crippled by Miner’s Knee, Miner’s Hip, Miner’s Back. The rest were at home breathing bottled oxygen, their lungs ruined from inhaling coal dust. You’d have to call them moderately lucky, George reflected. The unluckiest were like his own father, keeled over in his own basement. Dead at fifty-four.

Nevertheless, “Bakerton Coal Lights the World” is also a very nearly true statement—it lights at least some portion of the world—and elicits a measure of pride.

When the mines opened, they drew a population precipitated out from the international migration flows of the early 20th century and created a town beside the mine. “English and Irish, then Italians and Hungarians; then Poles and Slovaks and Ukrainians and Croats.” The housing, by the standards of the day, was decent. The churches and the hospital and many of the stores were built of brick; they “seem built to last. Their brick facades suggest order, prosperity, permanence.” The mines are the basis of the lives the migrants come to know, the only lives their children ever knew:

On a good day the air smelled of matchsticks; on a bad day, rotten eggs. … On breezy days the whole town closed its windows, but no one ever complained. … The sulfurous odor meant union wages and two weeks’ paid vacation, meat on the table, presents under the Christmas tree.

Then the easy-to-reach coal is all mined out, and the hard-to-reach coal won’t sell at prices that justify the cost of extracting it. The mines close. So do many of the local businesses. Eventually, too, some of the churches.

When the coal is gone and natural gas becomes the fossil fuel du jour, coal remains Bakerton’s nostalgically remembered first love. Coal was labor intensive, employing hundreds or thousands of men at a time for decades. Natural gas takes only a burst of labor to drill the well and doesn’t need many workers after that. The drillers—Herc and Mickey and Jorge and their crewmates—are temporary residents, drilling Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale now, after coming from a different pocket of gas elsewhere before, going to yet another pocket of gas in yet another state next. Their lives are not rooted in the place the way the miners’ were. They are housed in a temporary work camp, no families in tow. The miners’ children and grandchildren who remain in Bakerton resent the transient workers, who earn more than most of the locals, bring traffic congestion where there had been none, and crowd the stools and introduce new tensions at a favorite local bar.

Even so, gas leases look at first like an appealing opportunity to some of the local landowners, a supplemental source of income that can be derived from property they already possess. Some farm, or aspire to farm, the land and the economics of family farming are tough. Rich Devlin hopes the revenue from the gas lease he signs will pay for a Honiger 4000 milking system, his starting investment for a new dairy operation. By contrast, his neighbors, Rena and Mack, run the dairy farm already established by Mack’s father and have made the finances work in part thanks to Rena’s income from her nursing job and in part by pursuing organic farming and selling their product at a higher price to upscale consumers in Pittsburgh. Though Mack is intrigued by the promised gas lease payments, Rena points out that their organic production standards are threatened by having extractive industry next door potentially contaminating their water, never mind inviting it onto their very own land.

Then, in a matter of a handful of years rather than generations, the same price calculation that closed the coal mine sends the frackers packing, leaving new flavors of environmental devastation in their wake. Perhaps they will be back when the ratio between drilling costs and natural gas prices changes again; perhaps not.

The romance of coal was not based on denial. The community knew the injuries they suffered, and the role coal mining played in their pain. But if they loved and respected their neighbors and themselves, as they mostly managed to do, that means they loved and respected people whose lives were shaped by coal. When he was a boy, Rich Devlin read avidly about the American Indian nations of the region and imagined the place he lived without the coal town infrastructure, without “the sprawling strip mines that blackened the earth like char.” But as an adult, his interest in that lost landscape faded. “If not for the mines, he’d be someone else, somewhere else. He’d never know this place existed, and so, for him, it wouldn’t.”