Fighting Climate Change in Portlandia

Not only is failure not an option, those fighting to avert cataclysmic climate change have achieved important successes worthy of celebrating.

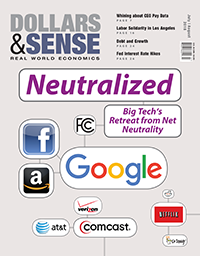

When the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) decided in 2015 to regulate Internet providers through "net neutrality" principles, the conservative Wall Street Journal predicted a "Telecom Backlash." The great regional cable monopolies like Comcast and AT&T, as well as the wireless carriers like Verizon and Sprint, opposed the net neutrality orders because they would prevent them from further monetizing their control over the "pipes" that online data takes to reach end users. With the advent of the Trump administration, they ultimately got their way, as the FCC reversed itself on December 14, 2017 and undid the crucial "Title II" classification, which made broadband a telecommunication service rather than an information service, and therefore allowed the FCC to impose net neutrality-based regulations.

Meanwhile, the giant tech companies, like Facebook and Google's subsidiary YouTube, are usually viewed as supportive of Title II, and they had meaningfully opposed the telecoms earlier this decade in support of neutrality. However, Silicon Valley's growing dominance is drawing it into the telecommunication industry itself, diminishing its support for the popular neutrality principles. This change has the potential to reshape Internet access, a pivotal development with ramifications for the entire U.S. economy.

The basic argument for net neutrality is relatively easy to understand. The main principle is that information traveling over a network shouldn't be subject to discrimination or favor, like speeding up the data flow for companies that can afford to pay the network operator, or slowing down (or even blocking) info from entities the operator doesn't care for. This basic principle has long applied to many familiar networks, like the traditional phone system. When you make a phone call for pizza delivery, for example, the mobile carriers can't steer your call to another pizzeria that paid for the privilege. They have to connect you to the one you dialed, and maintain a common standard of call quality. With the Internet's rapid growth over the last 20 years and its deep integration into our social, political, and economic lives, the stakes for abandonment of these principles online are very high. Net neutrality activists have argued that leaving the cable monopolists and the cell carrier oligopolists a free hand allows them to consider collecting unearned "rent" income by charging popular, cash-flush sites higher rates for faster or more consistent content delivery, while slowing down (or "throttling") content from poorer or unfavored sites. It gives the telecom industry enormous discretionary power.

The issue came to real national attention in 2014, when rising media giant Netflix refused to pay telecom colossus Comcast for the rising proportion of its traffic coming from users streaming its library of TV shows and movies. In retaliation, Comcast throttled Netflix data, causing users of its service to experience prolonged wait times with downgraded quality. This became popularly associated with the "spinning wheel of death" displayed as Netflix's content streamed through relatively tiny network connections. This was a risky move for Comcast, as it came between America and its TV shows--about as smart as stepping between a bear and her cubs.

Historically, the FCC had been unable to impose neutrality standards on the industry since Internet access was technically classified as an information service, rather than a telecommunication service. If it were reclassified as a telecom service, the cable and wireless firms' data plans could be designated "common carriers" like the traditional phone lines, considered to be too important to the economy to be unregulated. This reclassification would subject Internet service to Title II of the Telecommunications Act, which would effectively impose net neutrality norms on the industry. The FCC did this in 2015, and undid it in 2017.

The first of three rounds of battle over neutrality in the United States began before the Netflix debacle, in December 2010, and was indicative of the FCC's long-standing reputation as a "captured" regulator. The FCC's then-chairman, Tom Wheeler, was a former cable industry lobbyist, and unsurprisingly, the FCC's first attempt at a neutrality policy was literally written by people from the industry.

This FCC order was prepared by lobbyists and attorneys for AT&T, Verizon, and Google, and actually did ban the net neutrality violations of blocking and discrimination among data transmission. But a gigantic omission pointed toward the reason for the phone corporations' participation: The rule confined itself to the "wired" Internet, completely exempting service via a wireless signal. Liberal legal scholar Tim Wu, coiner of the term "net neutrality," observed the significance of this exemption in his fine book The Master Switch: "That enormous exception--AT&T and Verizon's condition for support of the rule--is no mere technicality, but arguably the masterstroke on the part of [the cell carriers]. It puts the cable industry at a disadvantage, while leaving the markets on which both AT&T and Verizon have bet their future without federal oversight."

Wireless was correctly understood at the time to be the growth center of the industry, so this exemption gave the cell service oligopoly a free hand to charge for prioritization and block content they didn't care for. Still, the telecom companies saw even the limited rules about wired Internet to be an infringement on their corporate liberty, and their major trade associations, the United States Telecom Association and the National Cable & Telecommunications Association, filed lawsuits immediately after the decision. The regulation, the Open Internet Order 2010, was ultimately struck down in court in 2014, leading to the next round of the struggle.

To understand the second round of net neutrality confrontation, we need to look at the corporate forces on either side of the issue. On one side were the great telecom giants, with AT&T, Comcast, and Verizon opposing net neutrality so they could charge more for choice access to their "bandwidth," or data flow capacity. Household-name tech platforms like Google, Facebook and Amazon were on the opposing side, eager to continue their rapid online growth without increased costs for access to the telecom networks.

In November 2014, President Obama recorded a video statement calling for Title II reclassification, largely in response to a groundswell of public comments on the FCC's online submissions facility, reaching over four million and largely supporting net neutrality. This was the result of a major activist campaign, combining online and offline action (see my article in the July/August 2015 issue of Dollars & Sense). Unprecedented numbers of public comments poured into the FCC thanks to efforts by prominent media figures, but above all through the efforts of a new movement of activists engaged in consciousness-raising and organizing with others to formally recognize the new importance of the Internet and the need for broadband providers to be held to the same standards as the traditional phone system. These activists were up against the usual barriers of apathy and distraction, as well as the somewhat technical nature of the issue and the vague feeling that the free-flowing Internet somehow cannot be leashed. Their success in moving first President Obama and then the FCC's senior staff shows the quite real power of organized activism, power that will be needed on this issue and others for years to come.

Despite conservative claims of "regulatory overreach" by these bold activists, the FCC's 2015 neutrality order specifically elected to "forbear" using several of the regulatory tools of Title II, including price limits, and left several important issues unresolved. But it confirmed the main net neutrality provisions, and the FCC in its short-lived rules explicitly drew attention to the tsunami of public comments in justifying its decision: "Because the record overwhelmingly supports adopting rules and demonstrates that three specific practices invariably harm the open Internet--blocking, throttling, and paid prioritization--this order bans each of them, applying the same rules to both fixed and mobile broadband Internet access service."

A predictable chorus of conservative and neoliberal opposition quickly arose, led by Republican FCC commissioner Ajit Pai. Among the usual cant about overreach, Pai claimed no action was needed since "The Internet is not broken." Netflix subscribers watching the spinning wheel while Comcast and other cable firms were throttling its data capacity might disagree. For their part, the cable and cellular Internet service providers (ISPs) claimed that the threat of FCC interference will limit their infrastructure investments--meaning the networks would lay less cable and delay upgrading cell towers because of rising expenses or lower revenues. This oft-repeated claim was countered by reporting from the MIT Technology Review, which found that the telecom networks have a hilarious 97% profit margin on bandwidth investments. They're unlikely to walk away in the face of mild regulation--indeed, they haven't deserted European markets, where some network neutral provisions are in effect.

The Trump administration has amounted to a major setback for net neutrality, as it did for so many other important economic, social, and environmental policies. Trump appointed the leading Republican on the FCC, Pai, to head the agency, and he soon announced that the agency was reevaluating the Title II classification. Pai's main justification for doing so was his repeated claim that net neutrality was depressing investment in the telecommunications network, despite the industry's absurd profit rates. In fact, Comcast and other large broadband providers had continued to increase their capital investments in years since the FCC's neutrality rules were issued. On December 14, 2017, the commission voted to formally overturn the Title II ruling, despite continued telecom investment, and the lack of major competition among the cable companies that supply the wired broadband for Wi-Fi service.

Activism to save neutrality this time around was somewhat less dramatic than in the previous round, perhaps owing in part to the diminishing support of the influential tech titans. However, public comments poured in at the FCC once again, forcing them to "rate limit" submissions, ensuring tranches of comments were gradually submitted so as not to overwhelm their docket facility yet again. Twenty-three million comments were submitted by the time of the repeal vote, but many were clearly being generated by computer software programmed to churn them out. Many falsely alleged to have been submitted by public figures; others were posted under the names of dead or fictional people. Some of the fake comments supported net neutrality and Title II, but the Wall Street Journal reported that one anti-neutrality email was posted at "a near-constant rate--1,000 every 10 minutes--punctuated by periods of zero comments, as if web robots were turning on and off...The Comment has been posted on the FCC website more than 818,000 times." A report by telecom firms found many of the comments were attributable to "FakeMailGenerator.com." It's a pity that the public comment process at the FCC and other regulatory agency websites have been so heavily gamed.

So as of June 2018, net neutrality requirements are no longer in effect nationally in the United States. Exactly what this major reversal for freedom means as far as market conditions will take time to materialize. There are clues in coffee shops and with in-flight airline-sponsored Internet access, which are exempt from neutrality rules since the companies are not telecom firms and provide web access as a perk. There, tech giants like Amazon prominently sponsor the service, and users are steered toward certain sites, although differences in bandwidth access aren't yet common. On mobile, the telecoms have been experimenting for some time with "zero rating," a practice of not counting use of certain partner websites or services against a data plan. These modest neutrality violations can be expected to expand over time, likely leading to poorer service and restricted access for those less able to pay.

The dramatically waxing and waning fortunes of net neutrality owe a lot to the shifting stances of the giant tech platforms over neutrality. In the proposed 2010 rule written by industry, Google had agreed with Verizon that neutrality rules weren't even necessary on wireless systems. When Obama made his famous November 2014 video calling for Title II reclassification, Google founder Eric Schmidt told an administration official that the position was a mistake. Despite its alleged idealism, Google was among the first tech platforms to waver; as the Wall Street Journal put it, "Google and Net Neutrality: It's Complicated."

While in 2010 the tech giants directly signed on to the effort to support net neutrality, in 2014 they mostly left neutrality policy to their lower-profile Internet Association, their trade group. The National Journal found "big Web companies like Facebook and Google mostly stayed on the sidelines of the debate." Several prominent online companies did stage an "Internet Slowdown," replacing their normal home pages with a graphic of the spinning "loading" wheel, dramatizing the risks posed by fast- and slow-lanes. Participating firms included Web mid-weights like Mozilla, Kickstarter, WordPress, and of course Netflix. Notably absent were the heavyweights like Google, Facebook, or Apple.

In 2017, their support was thinner still, and some tech figures argued that the reclassification wasn't necessary for effective neutrality. The business coverage ran headlines like "Web Firms Protest Efforts to Roll Back Net Neutrality," but the fine print reveals the companies involved are led by second-tier firms like Netflix, Reddit, and GoDaddy. And Netflix itself, the very poster child for net neutrality, was "less vocal" on the subject after it worked out satisfactory commercial deals with the telecom giants to route its data. The Wall Street Journal bluntly reported that the company "says it is less at risk now that it is big enough to strike favorable deals with telecom companies. The company did just that, reaching several deals in recent years to pay broadband providers for ample bandwidth into their networks." And "some big players," including Google and Amazon, "were content with relatively low-key efforts."

While the smaller firms were purposely displaying the annoying pinwheel, Google couldn't be bothered to include the image on the front of its incredibly prominent search engine page. Instead, the firm ran a post on its relatively obscure policy blog, while Amazon deployed a noncommittal button linking to the FCC comment facility, and Facebook CEO Zuckerberg posted that he supported Title II but was "open to working with members of Congress." Hardly an aggressive stance. In 2017, the smaller online firms did reprise the deliberate display of the slow-loading pinwheel, but they were increasingly lonely among the towering tech colossi in doing so.

So why the reluctance to stick up for net neutrality again? After all, these firms do rely on open access to the telecom industry's "pipes" of the Internet to deliver their oceans of free user content to their platforms globally. The answer is clear economics: The companies are themselves becoming ISPs like the telecom companies, investing heavily in new cables and other infrastructure to bring content and their platforms' services to users. They are losing their previously stark opposing interest to the telecom giants, and indeed their interests increasingly overlap.

Big Tech has moved further in this direction since the 2014-15 struggle. The business media frequently report on these changes. In early 2016, the Wall Street Journal reported that Microsoft and Facebook were jointly investing in a transatlantic data cable to add redundancy to the networks their platforms rely on. Because the project cost hundreds of millions of dollars, "only the very largest Internet companies have made the plunge" into digital infrastructure on this scale. The deal indicated that "the biggest U.S. tech companies are seeking more control over the Internet's plumbing."

Amazon has also invested in another undersea bundle of fiber optic cables, and in late 2016, Facebook and Google announced major investments in a high-speed line between Los Angeles and Hong Kong. Google is also laying an incredible 6,200-mile-long fully private cable from LA to its data center in Chile, part of an effort to catch up to Amazon and Microsoft in cloud computing. Fascinatingly, a Google cloud computing exec is reported to claim the company's telecommunications infrastructure "adds up the world's biggest private network, handling roughly 25% of the world's internet traffic ... without relying on telecom companies." Except that now, Google is a telecom company.

Indeed, all the tech giants have invested in their own high-speed data lines between major world cities for years. These investments are intended to ensure enough capacity to route information among the giants' enormous data centers. The business press suggests, amazingly, that "the investments have pushed aside the telephone companies that dominated the capital-intensive market for more than a century." The process is strikingly reminiscent of Rockefeller's money-gushing Standard Oil empire, which first conquered energy, and then began taking over the rail lines carrying that energy. These market developments make it easy to understand why the big tech firms are less and less interested in confronting the telecom industry: They are increasingly members of that industry, and they are gaining an economic interest in the possibility of prioritizing or penalizing different data. They are gaining control. This is a major long-term trend that will see the future blurring of the lines between tech and telecom. Let this be a lesson to social and political movements: Capitalists are only social-change allies as long as it suits the bottom line.

Despite the blow to leftist and liberal morale from the Trump FCC's reversal and the spreading desertion of the mega-cap tech giants from the neutrality struggle, positive signs persist. Notably, in May 2018, Senate Democrats successful voted with a handful of Republicans to restore the Title II classification, a surprising victory but one doomed to die in the GOP-run House of Representatives. But the vote speaks to the enduring popularity of the idea. Net neutrality has a future in legislatures and administrations less devoted to the unfettered freedom of enormous cable monopolists to steer public attention away from war and economic inequality and toward pleasant corporate propaganda and pop songs.