The U.S. Care Affordability Crisis

Cuts in government spending and deportation threats against the workforce have sent costs soaring in daycare, eldercare, and long-term medical care.

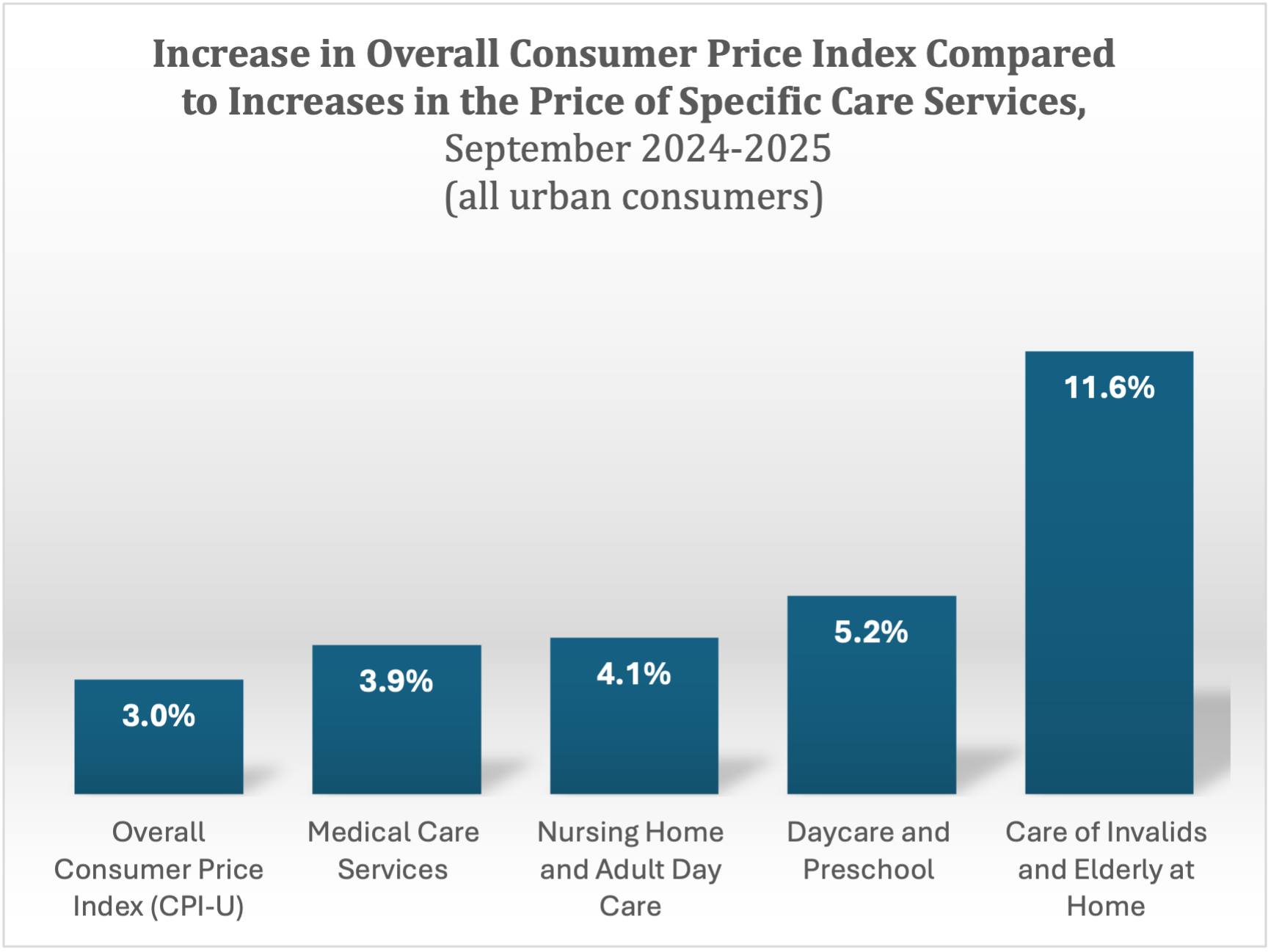

The price of purchased care services is rising much faster in the United States than the overall rate of inflation, intensifying the affordability crisis for those paying for the care of others as well as themselves.

If you were living in an average household and therefore purchased an average basket of goods and services (heavily weighted by expenditures on food, housing, and transportation) you shelled out 3% more for that basket in September 2025 than in September 2024.

However, if you lived in a household that had significant care expenditures, you experienced a higher rate of inflation, as indicated by the chart above. Prices for daycare and preschool and for the care of invalids and the elderly at home went up particularly rapidly. Since these expenditures vary considerably over people’s lifetimes, some households spend far more on them than others in a given year.

The shortage of affordable childcare has gotten a lot of publicity lately, because it prevents many parents of young children from earning the money they need to cover their rent, food, and gas. The demands of unpaid care for disabled and frail family members are less predictable, but they too reduce opportunities for women, in particular, to participate in paid employment. Their household’s disposable income often goes down whether or not they purchase care services—either as a result of higher prices or lower earnings.

Public policies rely heavily on the overall Consumer Price Index (CPI). Eligibility for publicly subsidized childcare, like eligibility for housing and fuel assistance and the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP), is based on a comparison of inflation-adjusted family income with inflation-adjusted poverty lines, without full consideration of care expenses.

As an important new report from the U.S. Census office explains, both the official poverty line and the more comprehensive Supplemental Poverty Measure underestimate the costs of caring for young children and therefore understate the number of families with young children living in poverty.

Likewise, eligibility for subsidized medical and nonmedical care for people experiencing disability or frailty through the Medicaid program is based on levels of inflation-adjusted family income that don’t explicitly consider either the price of care service purchases or the rapid escalation of their prices.

What are the forces driving disparate price trends? Care services are labor intensive and difficult to automate, a factor that I explore more fully in my forthcoming book, Making Care Work: Why Our Economy Should Put People First. Prices of care services have steadily outpaced the standard Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) since at least 1997.

Over the last year, however, two major policy changes have intensified this trend: cuts in public investment and the deportation and intimidation of immigrant employees.

Federal budget cuts have reduced eligibility for Medicaid and subsidies for the Affordable Care Act, increasing out-of-pocket costs and putting upward pressure on prices. Medicaid is a major source of public support for both nursing home care and the care of invalids and the elderly at home.

Federal budget cuts to both childcare and education have shifted burdens for public provision to the states, many of which are being forced to cut back on services. The full impact of these cuts is likely to become more evident in the months to come.

The cumulative impact of official anti-immigration policies is also likely to grow. Both legal and undocumented immigrants represent a large share of the workforce in childcare and elder/disability care. Previous efforts to deport undocumented workers through the Secure Communities Program initiated in 2008 were unevenly distributed across communities, making it possible to assess comparative outcomes. Considerable research shows that the program tended to reduce the supply of paid workers in nursing homes, childcare centers, and home-based care provision, often with negative consequences for care quality.

Undocumented workers have long been particularly likely to find jobs in the informal sector as household employees, and their greatly reduced entry into the United States (as well as threats of deportation), helps explain why the rate of increase in the cost of purchased care for invalids and the elderly at home reached 11.6% between September 2024 and September 2025.

Undocumented workers also found a big niche in gardening services. I didn’t include the price of these services in the chart above, since they don’t represent a form of direct care for people who need assistance. However, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics news release cited above, their price increased 13.9% over the 12-month period—a pattern that drives home the impact of draconian immigration policies.

As much as I love lawns and gardens, however, I’m more worried about the future of care for our families, friends, and neighbors.

Nancy Folbre is professor emerita of economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Her research explores the interface between political economy and feminist theory.