Fighting Climate Change in Portlandia

Not only is failure not an option, those fighting to avert cataclysmic climate change have achieved important successes worthy of celebrating.

The Fed’s rate cut is likely to have little impact on mortgage interest rates. The reason is straightforward but rarely recognized in the abundant flow of commentary on Fed policy.

The Trump administration’s fulminations leading up to the September 17 meeting of the Federal Reserve’s policymaking committee was almost certainly unprecedented in the 112-year history of the U.S. central bank. By contrast, the outcome of the meeting was a tame anticlimax. The Fed policymakers voted to lower the short-term interest rate that it controls—the “federal funds rate”—by one-quarter point, from a range of 4.25–4.5% to 4.0–4.25%. They also signaled that more small cuts in this policy rate that it controls are likely coming.

Prior to this Fed meeting, President Donald Trump had been bashing Federal Reserve Board chair Jerome Powell for months, as, among other insults, a “moron” for not lowering interest rates as Trump had demanded. Failing to move Powell, Trump and his henchmen pivoted to concocting false and malicious accusations of illegal financial dealings against Fed Board member Lisa Cook. Trump was aiming to force Cook to resign, or, failing that, to fire her “for cause” prior to the September 17 Fed meeting. But Cook refused to buckle. The courts have also ruled, at least so far, that Trump has no legal case for firing Cook.

Trump did still get one victory prior to the September 17 Fed meeting. Only two days before the big meeting, Trump managed to fill the one vacancy on the Fed Board with Stephen Miran, one of his minions. In an unprecedented move, the Republican-controlled Senate rammed through Miran’s confirmation after having conducted virtually no oversight.

Amid these various norm-busting developments, much less attention has been paid to how the Fed’s decision at the September 17 meeting will actually impact the economy. Of course, this is the only question that really matters when our concern is the economic well-being of the country’s overwhelming majority of non-rich people.

Let’s focus for now on one specific question: What does the Fed’s September 17 cut in their policy interest rate mean in terms of the mortgage rates that people will face when they borrow to buy a home or to refinance a home they already own? The question is especially pertinent, given that housing costs in the United States have become increasingly unaffordable. By one key measure, average house prices have increased by over 50% since 2020. Correspondingly, the National Association of Home Builders estimates that 77% of households cannot afford to buy a house at the 2024 median price of $500,000.

In fact, the Fed’s rate cut is likely to have little, if any, impact on mortgage interest rates. The reason is straightforward but rarely recognized in the always abundant flow of commentary on Fed policy. That is, in using its standard tool of adjusting its policy interest rate up or down, the Fed simply does not have the power to control all other interest rates in financial markets.

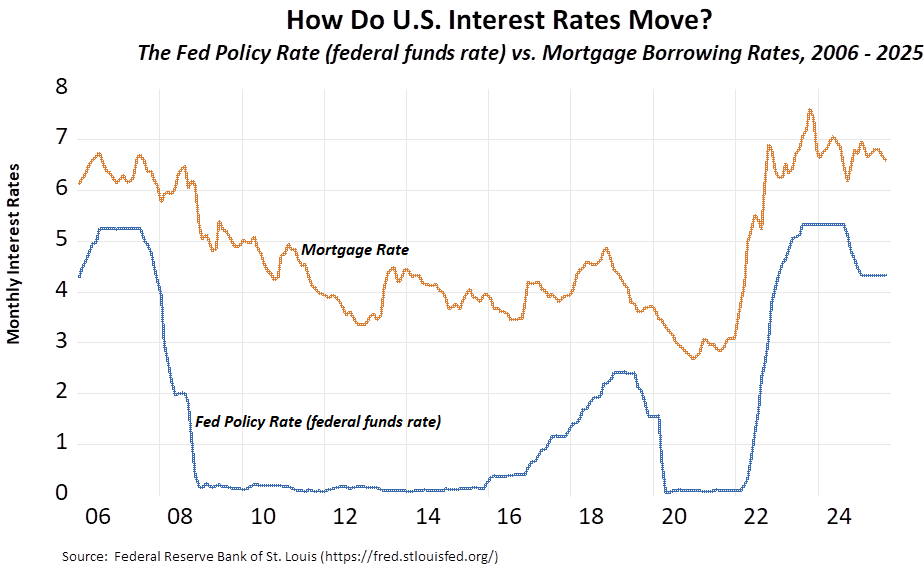

We can see this clearly when we consider the movements of the interest rate on mortgages alongside the changes in the Fed’s policy rate. The figure below tracks these relative movements from just prior to the 2007-2009 financial crisis to the present.

Between mid-2007 and the end of 2008, the Fed dropped its policy rate from 5.3% to near zero, an historically unprecedented move aimed at staving off an impending financial collapse and 1930s-level depression. Over this same period, the average interest rate on mortgages also declined, but only from 6.7% to 5.3%. The Fed then maintained its policy rate at near-zero for nearly seven years, until the end of 2016. Yet over that period, the interest rate on mortgages still averaged 4.1% and fluctuated only modestly.

The pattern was similar during the 2020–2022 COVID lockdown. Starting in April 2020, the Fed again dropped its policy rate from 2.0% to near-zero and maintained the near-zero rate until mid-2022. Over this period, the interest rate on mortgages also declined, but only slightly, from 3.6% pre-COVID lockdown to an average of 3.3% from mid-2000 to mid-2022.

The point is that mortgage lenders, as with all other bankers, are in business to make profits. They set mortgage rates based on what they think the market will bear, given factors such as their best guesses on, among other things, future inflation and the chances of borrowers stiffing them. How the Fed chooses to move its policy interest rate up or down is only one consideration in the overall mix.

It follows that if we want to make home buying more affordable, we need to work with a more effective set of policy tools than just moving the Fed’s policy interest rate up or down. In fact, it is not difficult to envision such an alternative policy framework. On a few occasions—in particular during the 2007–2009 and 2020–2022 financial crises—the Fed has utilized additional policy tools that can more effectively impact a broader set of interest rates, including mortgage lending rates.

Still more, the financial regulatory system that prevailed in the United States from the 1930s to the 1970s, the Glass-Steagall system, was broadly successful in delivering affordable housing to the U.S. middle class, among other achievements. The Glass-Steagall system worked by creating regulated financial institutions, including Savings and Loan Associations—targeted at maintaining a stable market for affordable mortgages. But a return to an updated variant of this earlier regulatory system will require moving far beyond the histrionics and personal slander that pass as Fed policy deliberations by Trump and company.