[N.B.: First three items by our fabulous summer intern Elizabeth Murphy, who also chose this post's Possibly Irrelevant Image. Sorry for the delay posting these!]

[N.B.: First three items by our fabulous summer intern Elizabeth Murphy, who also chose this post's Possibly Irrelevant Image. Sorry for the delay posting these!]

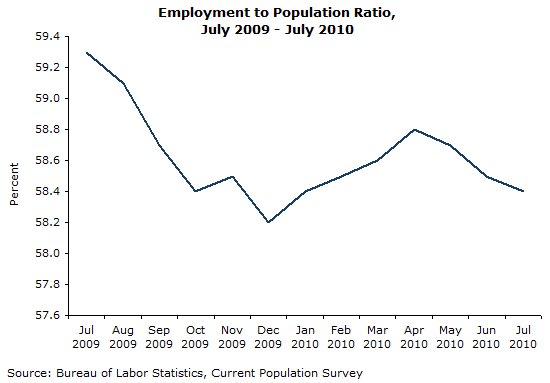

(1) The Bureau of Labor Statistics released the July unemployment numbers last Friday (Aug.6) and they do not look pretty.

Unemployment remains exactly where it was at the end of the recession at 9.5%, with 14.6 million unemployed persons. The Center for Economic and Policy Research writes,

"For the second consecutive month, the economy created virtually no jobs, net of temporary Census jobs. The Labor Department reported that the economy lost 131,000 jobs in July, 12,000 less than the 143,000 drop in the number of temporary Census workers. The June numbers were revised down by 100,000 to show a gain of only 4,000 non-Census jobs."

If anyone is looking for a more in-depth look at the unemployment figures, you should check out the Economic Policy Institute's Economy Track. They have an interactive map of the U.S. which details unemployment figures for each state. Nevada is still the state with the highest unemployment at 14.2%.

--Elizabeth Murphy

(2) According to some statistics, theses unemployment figures correspond with an ongoing trend in U.S. economic recovery. Pragmatic Capitalism offers Some Perspective on the High Unemployment Rate:

"Assuming that the recession ended in June 2009, the current unemployment rate is exactly where it was at the end of the recession (9.5%). For some perspective on the current state of the labor market, today’s chart illustrates the amount of time it took for the unemployment rate to ultimately dip below (and stay below) its recession-end level for each recession since the late 1940s. For example, at the end of the recession that ended in November 1982, the unemployment rate stood at 10.8%. As the chart illustrates, it took two months for the unemployment rate to drop below (and stay below) the recession-end level of 10.8%. It is noteworthy that, over the past two decades, it has taken significantly longer (on average) for the unemployment rate to drop below its recession-end level. The reasons for this increased time for the unemployment rate to turn around varies. However, one explanation has it that following World War II, the US found itself in a strong/dominant economic position. It took time, but eventually many of the remaining world economies began to recover and we are currently witnessing increased competition as a result of the rise of the rest."

The article (by Chart of the Day) includes a great chart showing how long it took after each recession for unemployment levels to drop below recession end levels starting in 1949. It shows that in 2001, it took nearly 36 months!

--Elizabeth Murphy

(3) As worrying as these unemployment figures are, even more worrisome is the lack of action being taken to fix unemployment. Brad Delong vents his frustration at TheWeek.com:

Instead, we have the Obama administration calling for a three-year spending freeze on programs unrelated to national security. We have Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee chairman Chris van Hollen calling for deeper short-term spending cuts. We have an administration experiencing difficulty finding $23 billion to prevent additional teacher layoffs, even though maintaining — no, expanding — investment in education in a recession is the no-brainiest of no-brainers.

Why the enormous disconnect?"

A calm, passive approach to unemployment is not going to help improve these unemployment figure, but panic probably won't help much either. Delong ends his article with interesting and unnerving questions. And as far as the last question is concerned, I sincerely hope the answer is no: "Are we passively watching an unrepresented underclass of the long-term unemployed created before our eyes?"

--Elizabeth Murphy

(4) Today's New York Times has an interesting article, Rates Fall as Market Fears Economic Weakness, suggests that bond traders, far from being "bond vigilantes" pressuring governments toward austerity, may actually be worried that deficit hawks are leading us to a double-dip recession:

That market reaction is the opposite of what happened in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Then “bond vigilantes” were reluctant to invest in United States Treasury securities because they feared runaway inflation. Their refusal drove up the interest rates the government had to pay on its borrowings and eventually led the Federal Reserve, under Paul A. Volcker, to wage war against inflation even if it meant choking off economic growth.

Now, far from showing a reluctance to finance the American government, investors are seeking safety and evidently believe American government debt is the safest possible investment. They have rushed to send money to the Treasury, thereby reducing borrowing costs for the government.

By late 2009, interest rates had fallen to levels previously thought inconceivable. The annual yield on a two-year Treasury note dipped below 1 percent. But it has since traded barely above one-half percent.

Perhaps investors are nervous because they fear governments will swing too far toward austerity. When economies weakened three years ago, talk immediately turned to economic stimulus. This time, much of the discussion in Washington, as well as in many European capitals, has focused on the need to reduce spending and deficits, rather than on the possibility that additional stimulus might be needed to avert a new worldwide downturn.

And the article concludes:

But for now, the financial markets seem to fear recession and deflation much more than they fear deficit spending.

Maybe the markets are smarter than we thought, this time around?

--Chris Sturr