2 min read

We are finally done (mostly) with our September/October issue. (We won't be sending it to e-subscribers until Monday.) It's our annual labor issue, and I'm quite pleased with it! Here is our p.2 editorial note:

How can people exercise more power over their lives at work? Most workers, bargaining individually with their employers, have very little power over even the traditional aspects of the employment bargain—wages, benefits, hours, and so on. People who have exceptional skills (such as star athletes or entertainers), or at least are thought to have such skills (top executives), obviously, can drive the hardest bargain. The workers at the “bottom” of the occupational hierarchy typically exercise the least control. That’s why those jobs are poorly paid, with scant benefits, and poor working conditions (including widespread workplace abuses).

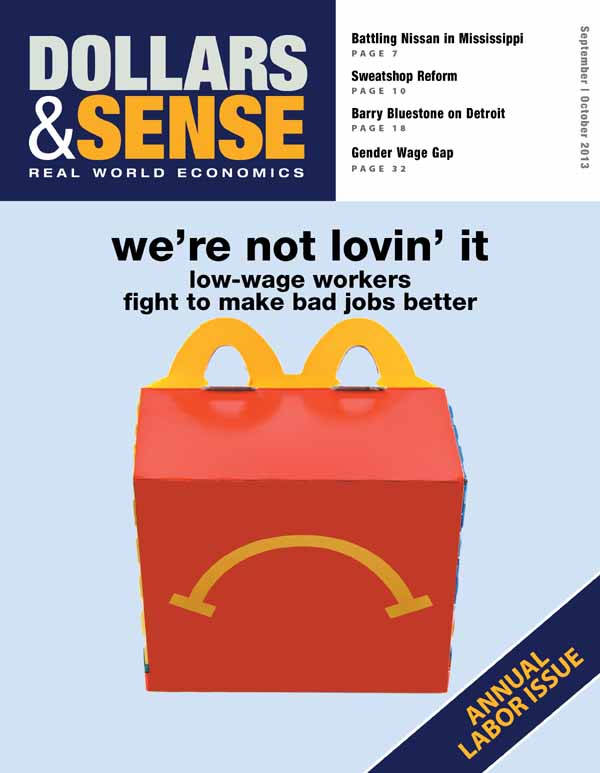

With over thirty years of wage stagnation and the steady decline of the labor movement, more and more jobs are “bad jobs.” “A growing number of Americans are realizing that ‘good jobs’ aren’t coming back,” writes sociologist Nicole Aschoff, “and that McJobs are the jobs of the future.” That’s not breeding complacency, though, and may in fact be a key realization behind the recent upsurge of activism among low-wage workers. Workers in what have been low-wage service jobs—especially at corporate giants like McDonalds and Walmart—are visibly picketing, protesting, and striking. They’re fighting to make bad jobs better—to raise wages, get better benefits, get more job security, and end abuses like wage theft.

These traditional objects of collective bargaining are not the end-all be-all of labor organizing. U.S. unions have, at least since the end of the Second World War, focused narrowly on wages and benefits. We need, however, to focus more clearly on what management insisted (and unions agreed) was to be a no-fly zone: the control of the workplace and the production process. Management’s insistence on cutting labor out of any input into product quality, labor productivity, and technological innovation—as economist Barry Bluestone argues in his reflections on the long-term decline of Detroit—was part of what doomed the auto industry and ultimately the city.

One answer would be for workers and unions to bargain with employers over the control of the labor process itself. But workers don’t have to bargain with ownership or management if they are the ownership and management of their own enterprises. Economist Nancy Folbre takes a look at why worker-owned, worker-managed cooperatives are not more prevalent in capitalist economies or, more accurately, why they are more prevalent in some regions and industries than others. And she identifies some key ingredients—more widespread understanding of cooperative principles, more worker experience in democratic workplace governance, and more cooperative support for other cooperatives—for the stability, growth, and proliferation of worker co-ops.

Rounding out the issue: economist and D&S co-editor Alejandro Reuss looks at our “triple jobs problem”—lethargic job creation, persistent unemployment holding down workers’ bargaining power, and anti-worker policies that keep labor weak even when labor markets are “tight.” Labor journalist Roger Bybee looks at the grassroots movement for better jobs at Nissan’s new Mississippi plant. And economist Gerald Friedman looks at the male-female pay gap, the progress women workers have made relative to men, and why there is still a long way to go to achieve full equality.

Last week we posted Alejandro Reuss's comment, Our Triple Jobs Crisis. And we have just posted Nicole Aschoff's cover story, We're Not Lovin' It: Low-Wage Workers Fight to Make Bad Jobs Better.

Enjoy!

--Chris Sturr