The American Dream, We Hardly Knew You

Worsening inequality leaves young adults worse off than their parents.

BY JOHN MILLER

If Americans’ hopes of getting ahead have dimmed, as the Wall Street Journal reports yet again, it could only be because the lid of the coffin in which the “American Dream” was long ago laid to rest has finally been sealed shut.

The promise that if you work hard and play by the rules, you will get ahead, or if you don’t, surely your children will, was broken long ago. And today’s economic hardships have left young adults distinctly worse off than their parents, and especially their grandparents.

This long decline has stripped away much of what there was of U.S. social mobility, which never did measure up to its mythic renderings. Let’s look closely at what the economic evidence, compiled in many meticulous studies, tells us about what passed for the American Dream, its demise, and what it would take to make its promised social mobility a reality.

The Long Decline

For at least two decades now, the Wall Street Journal has reported the dimming prospects of Americans getting ahead, each time with apparent surprise. In 2005, David Wessell presented the mounting evidence that had punctured the myth that social mobility is what distinguishes the United States from other advanced capitalist societies. A study conducted by economist Miles Corak put the lie to that claim. Corak found that the United States and United Kingdom were “the least mobile” societies among the rich countries he studied. In those two countries, children’s income increased the least from that of their parents. By that measure, social mobility in Germany was 1.5 times greater than social mobility in the United States; Canadian social mobility was almost 2.5 times greater than U.S. social mobility; and in Denmark, social mobility was three times greater than in the United States.

That U.S. social mobility lagged far behind the myth of America as a land of opportunity was probably no surprise to those who populated the work-a-day world of the U.S. economy in 2005. Corrected for inflation, the weekly wages of nonsupervisory workers in 2006 stood at just 85% of what they had been in 1973, over three decades earlier. An unrelenting increase in inequality had plagued the U.S. economy since the late 1970s. A Brookings Institution study of economic mobility published in 2007 reported that from 1979 to 2004, corrected for inflation, the after-tax income of the richest 1% of households increased 176% and increased 69% for the top one-fifth of households—but just 9% for the poorest fifth of households.

The Economist also found this increasing inequality worrisome. But its 2006 article, “Inequality and the American Dream,” assured readers that while greater inequality lengthens the ladder that spans the distance from poor to rich, it was “fine” if it had “rungs.” That is, widening inequality can be tolerated as long as “everybody has an opportunity to climb up through the system.”

Definitive proof that increasing U.S. inequality had not provided the rungs necessary to sustain social mobility came a decade later.

The American Dream Is Down for the Count

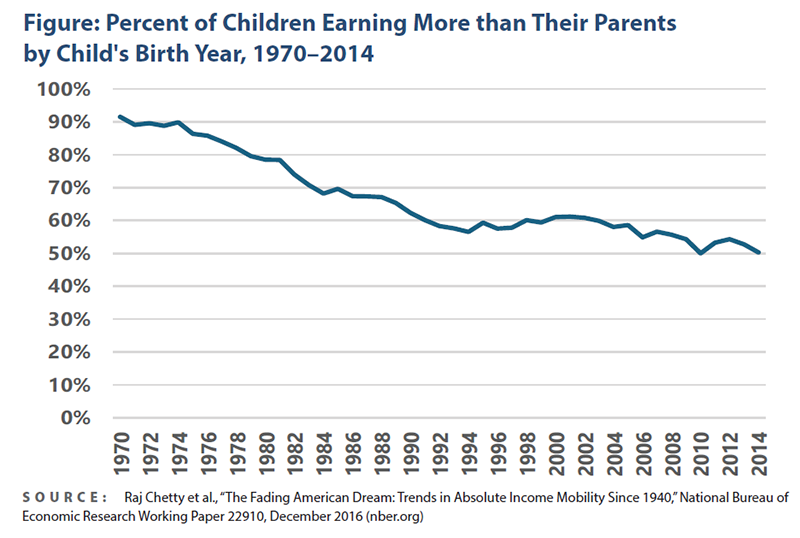

In late 2016, economist Raj Chetty and his multiple coauthors published their study, “The Fading American Dream: Trends.” They documented a sharp decline in mobility in the U.S economy over nearly half a century. In 1970, the household income (corrected for inflation) of 92% of 30-year-olds (born in 1940) exceeded their parents’ income at the same age. By 1990, just three-fifths (60.1%) of 30-year-olds (born in 1960) lived in households with more income than their parents earned at age 30. By 2014, that figure had dropped to nearly one-half. Only 50.3% of children born in 1984 earned more than their parents at age 30. (The figure below depicts this unrelenting decline in social mobility. It shows the relationship between a cohort’s birth year, on the horizontal axis, and the share of the cohort whose income exceeded that of their parents at age 30.)

The study from Chetty and his co-authors also documented that the reported decline in social mobility was widespread. It had declined in all 50 states over the 44 years covered by the study. In addition, their finding of declining social mobility still held after accounting for the effect of taxes and government transfers (including cash payments and payments in kind) on household income. All in all, their study showed that, “Severe Inequality Is Incompatible With the American Dream,” to quote the title of an Atlantic magazine article published

at the time. Since then, the Chetty group and others have continued their investigations of inequality and social mobility, which are available

on the Opportunity Insights website (opportunityinsights.org).

The stunning results of the Chetty group’s study got the attention of the Wall Street Journal. The headline of Bob Davis’s December 2016 Journal article summed up their findings succinctly: “Barely Half of 30-Year-Olds Earn More Than Their Parents: As wages stagnate in the middle class, it becomes hard to reverse this trend.”

Davis was correct to point to the study’s emphasis on the difficulty of reversing the trend of declining mobility. The Chetty group was convinced “that increasing GDP [gross domestic product] growth rates alone” would not restore social mobility. They argued that restoring the more equal distribution of income experienced by the 1940s cohort would be far more effective. In their estimation, it would “reverse more than 70% of the decline in mobility.”

Social Mobility Has Gotten Worse, Not Better

Since 2014, neither U.S. economic growth nor relative equality has recovered, let alone returned to the levels that undergirded the far greater social mobility of the 1940s cohort. Today, the economic position of young adults is no longer improving relative to that of their parents or their grandparents.

President Donald Trump was fond of claiming that he oversaw the “greatest economy in the history of our country,” during his first term (2017–2020). But even before the onset of the Covid-19-induced recession, his economy was neither the best nor good, especially when compared to the economic growth rates enjoyed by the 1940s cohorts who reached age 30 during the 1970s. During the 1950s and then again during the 1960s, U.S. economic growth averaged more than 4% a year corrected for inflation, and it was still growing at more than 3% a year during the 1970s. From 2015 to 2019, the U.S. economy grew a lackluster 2.6% a year and then just 2.4% a year during the 2020s (2020–2024).

Also, present-day inequality continues to be far worse than in earlier decades. In his book-length telling of the story of the American Dream, Ours Was the Shining Future, journalist David Leonhardt makes that clear. From 1980 to 2019, the household income of the richest 1% and the income of the richest 0.001% grew far faster than they had from 1946 to 1980, while the income of poorer households, from the 90th percentile on down, grew more slowly than they had during the 1946 to 1980 period. As a result, from 1980 to 2019, the income share of the richest 1% nearly doubled from 10.4% to 19%, while the income share of the bottom 50% fell from 25.6% to 19.2%, hardly more than what went to the top 1%. Beyond that, in 2019, the net worth (wealth minus debts) of median, or middle-income, households was less than it had been in 2001, which, as Leonhardt points out, was “the longest period of wealth stagnation since the Great Depression.”

No wonder the American Dream took such a beating in the July 2025 Wall Street Journal-NORC at the University of Chicago poll. Just 25% of people surveyed believed they “had a good chance of improving their standard of living,” the lowest figure since the survey began in 1987. And according to 70% of respondents, the American Dream no longer holds true or never did. That figure is the highest in 15 years.

In full carnival barker mode, Trump is once again claiming “we have the hottest economy on Earth.” But the respondents to the Wall Street Journal-NORC poll aren’t buying it. Just 17% agreed that the U.S. economy “stands above all other economies.” And more than twice that many, 39%, responded that “there are other economies better than the United States.” It’s a hard sell when the inflation-adjusted weekly wages of nonsupervisory workers are still lower than what they had been in 1973, now more than half a century ago.

And economic worries are pervasive. Three-fifths (59%) of respondents were concerned about their student loan debt, more than two-thirds (69%) were concerned about housing, and three-quarters (76%) were concerned about health care and prescription drug costs.

Rising housing costs have hit young adults especially hard. The median price of a home in 1990 was three times the median household income. In 2023, that figure had reached nearly five times the median household income. And the average age of a first-time homebuyer had increased from 29 in 1980 to 38 in 2024.

Finally, in their 2023 study, sociologists Rob J. Gruijters, Zachary Van Winkle, and Anette E. Fasang found that at age 35, less than half (48.8%) of millennials (born between 1980 and 1984) owned a home, well below the 61.6% of late baby boomers (born between 1957 and 1964) who had owned a home at the same age.

Dreaming Big

In their 2016 study, the Chetty group writes that, “These results imply that reviving the ‘American Dream’ of high rates of absolute mobility would require economic growth that is spread more broadly across the income

distribution.”

That’s a tall order. Fundamental changes are needed to confront today’s economic inequality and economic woes. A progressive income tax with a top tax rate that rivals the 90% rate in the 1950s and early 1960s would be welcomed. But unlike the top tax rate of that period, the income tax should tax all capital gains (gains in wealth from the increased value of financial assets such as stocks) and tax them as they are accumulated and not wait until they are realized (sold for a profit). Also, a robust, fully refundable child tax credit is needed to combat childhood poverty, as are publicly supported childcare, access to better schooling, and enhanced access to higher education. Just as important is enacting universal single-payer health care and increased support for first-time homebuyers.

The belief that “their kids could do better than they were able to,” was what Chetty told the Wall Street Journal motivated his parents to emigrate from India to the United States. These fundamental changes could make the American Dream the reality that it never was.

Sources: David Wessel, “As Rich-Poor Gap Widens in the U.S., Class Mobility Stalls. Those in Bottom Rung Enjoy Better Odds in Europe; How Parents Confer an Edge,” Wall Street Journal, May 13, 2005 (wsj.com); Miles Corak, “Do Poor Children Become Poor Adults? Lessons from a Cross-Country Comparison of Generational Earnings Mobility,” IZA DP Discussion Paper Series, no. 193, 2006; “Inequality and the American Dream,” The Economist, June 15, 2006 (economist.com); “The rich, the poor and the growing gap between them,” The Economist, June 15, 2006 (economist.com); Isabell Sawhill et al., “Economic Mobility: Is the American Dream Alive or Well?” The Economic Mobility Project, An Initiative of the Pew Charitable Trust, May 2007 (pew.org); Raj Chetty et al., “The Fading American Dream: Trends in Absolute Income Mobility Since 1940,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 22910, December 2016 (nber.org); Bob Davis, “Barely Half of 30-Year-Olds Earn More Than Their Parents,” Wall Street Journal, December 8, 2016 (wsj.com); Raj Chetty et al., “Only Half of 30-year-old Americans earn more than their parents,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, December 9, 2016 (equitablegrowth.org); Alana Semuels, “Severe Inequality Is Incompatible With the American Dream,” The Atlantic, December 10, 2016 (theatlantic.com); David Leonhardt, Ours Was the Shining Future: The Story of American Dream (Random House, 2023); Lindsay Ellis and Aaron Zitner, “Americans’ Hopes for Getting Ahead Dim,” Wall Street Journal, September 2, 2025 (wsj.com); Steve Rattner, “American Dream Charts,” Morning Joe, MSNBC, September 4, 2025 (stevenrattner.com); Rob J. Gruijters, Zachary Van Winkle, and Anette E. Fasang, “Life Course Trajectories and Wealth Accumulation in the United States: Comparing Late Baby Boomers and Early Millennials,” American Journal of Sociology, September 2023.