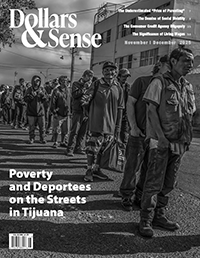

Poverty and Deportees on the Streets in Tijuana

Photos by David Bacon and an Interview with Laura Velasco

In the U.S. media, even in progressive media, we pay very little attention to what happens to most people when they’re deported, or when they choose self-

deportation as a result of fear. Most people who are deported or who self-deport go home to communities far south of the border. But the people who are just dumped through the border gate and have no home to go to find themselves in cities like Tijuana, Mexico. For many years, deportees from the United States have lived on the street or in the concrete Tijuana River channel.

November/December 2025 issue.

A year ago, the city’s refuges were packed with families from places as far away as Venezuela and Haiti. These days, that wave of people from countries besides Mexico has dissipated. People know that President Donald Trump has closed the border. These photographs show the cavernous halls in shelters where migrants set up their tents. Today shelter residents are often families from southern Mexico, fleeing the violence. Others are still here because they cannot go home. These photographs also show deportees mixed with other street dwellers, waiting in line to eat at a sidewalk meal distribution site. This is a terrible reality for many people.

These photographs try to document the lives of people on the ground in Tijuana. To give them a deeper context, I interviewed Laura Velasco, an investigator and professor at Tijuana’s Colegio de la Frontera Norte. Velasco has researched the situation of deportees and migrants in the city for many years, and has written several books about them.

Since U.S. policy is in great part responsible for the fact that migrants are here in the United States to begin with, it is our responsibility to look at what’s happening to them and take the Mexican reality into account. Mexico, with far fewer resources than the United States, has made much greater efforts to treat migrants as human beings. As the photographs and Velasco’s analysis show, the situation for deportees and self-deportees in Tijuana is mixed—people ripped from their lives at home, trying to survive as best they can. —David Bacon

David Bacon: Has the Trump administration’s wave of immigration enforcement—the deportations and self-deportations—had an impact in Tijuana and in other border cities?

Laura Velasco: The number of people coming into Tijuana since January has dropped significantly. People are being deported directly to their places of origin, or are being sent to Mexico City. They are not leaving them at the border, to prevent them from re-entering the United States. The Mexican government has arranged with the United States to receive Mexican deportees far from the border, particularly at airports in and around Mexico City, and the government talks about the large numbers of deportees they’re receiving at the airports, but not at the border.

Foreigners are sometimes also received there, before they return to their countries of origin. In addition, since [the administration of former President Manuel] López Obrador, the Mexican government has also had a policy of preventing foreigners from arriving at the border.

I have many doubts about his figures, but [President Donald] Trump says that since he became president, they have deported a million people, or forced people to self-deport. Of course they are from all countries, but many are Mexican. Nevertheless, there is only a small flow of deportees through the border gates. In January we were preparing for deportations we expected would be massive, but they weren’t. Instead, only 20 or 50 people have been arriving every day. They set up a shelter run by the army, which was very well organized, but there were few deportees.

DB: When I was in Tijuana recently, I saw that the number of people in the shelters has gone down.

LV: There are far fewer people in shelters in Tijuana now. Before the beginning of January, there were far more. Today in the shelters, most of the people are internally displaced Mexicans. They’re not foreigners. Most came from [the states of] Michoacán and Guerrero, but Michoacán is the source for most here in Tijuana.

They leave home because of all the criminal violence, the forced recruitment of young people, and the disappearance of family members. Some have told us that organized criminals charged them for the privilege of working. For every hour worked in the lemon harvest, for instance, they had to make a payment. These are very poor people who had nothing, and the gangs just took it from them.

Displaced people basically depend on shelters. Families need food and the time to make decisions about what they’re going to do, whether they return to their place of origin or stay. Their family networks also help, especially money from relatives in the United States, who send them money for their tickets, for food, to pay for a hotel for a few days or the first few days of rent.

Nevertheless, fewer internally displaced people are arriving in Tijuana because the possibility of entering the United States has been shut off. People who have been displaced and would come to the border and think about crossing now have to face not only the threat of deportation but also imprisonment. That has discouraged many people.

People who have returned from the United States speak about terrible prison conditions, and their stories have spread widely. There’s much less incentive to cross the border and enter as an undocumented immigrant, since you can not only be deported but might also be thrown in jail. In that sense, we can say that the U.S. policy of intimidation has worked.

At the same time, the number of Mexican workers brought to the United States on H-2A and H-2B visas has increased enormously. Last year the State Department issued over 300,000 visas for agricultural workers alone. So on the one hand, Mexican workers who have a life and home in United States are deported, while on the other, hundreds of thousands of Mexican workers are imported under this exploitative labor program.

DB: In one of the shelters for unaccompanied youth, I talked with two brothers from Haiti who’d been there for two years, and a young woman from Guatemala who’d been there for months. What happened to the people who were living in the shelters before?

LV: Some people we talked with recently have been in shelters for three or four years. Young people especially can’t leave the shelter, and their emotional situation and quality of life is not good. For the people who have been waiting to cross, the situation is very difficult now. The program that allowed people to apply for asylum, especially young people, and then leave detention on parole, has been closed. Even those who were on the path to asylum are more or less trapped in Tijuana because Trump’s policy will not allow anyone to enter now, even the young people who before perhaps had a hope of finding their family in the United States. Waiting without hope, really.

That has stranded many people who were on the path to regularization through asylum, and some have sought to settle and live in Tijuana. Perhaps some still think that at some point things will change, that the border will reopen and they will be able to cross. But others have found a job, and a place to live. You can see women on the streets selling merchandise, fresh fruit or weavings and clothing. They are families who have settled in Tijuana and are staying.

Many have left the shelters because there they often have no autonomy, no privacy, and no ability to organize their time. They can’t make noise, they can’t listen to music, they can’t cook their food. If they have children, the children have to stop being free. It is a very hard life of discipline.

So even though they can barely manage, leaving the shelters allows them to have freedom, to be able to sleep whenever they want, to get up whenever they want, to listen to music, to have their children make noise. The transition from the shelters to becoming independent, staying in the city—it’s a change in quality of life. Even though they’re living in very poor housing and have very precarious jobs, they see it as a step forward.

Some shelters are less restrictive. The Embajadores shelter in Scorpion Canyon, in the photographs, has very comprehensive services, including a school. It’s a much more community-based model than many others that just provide food and shelter. There’s more community integration, and a different way of relating to the migrants. It’s a model that emerged from local civil society.

DB: For many years I’ve taken photographs and talked with deportees living on the streets and in the river channel. But recently it seems the number of people sleeping outside has grown.

LV: There have always been people living on the sidewalks in Tijuana, and we don’t have measurements or numbers that tell us exactly whether that number is increasing. But the mayor suddenly came to our research center a few months ago, asking us for help, because the number of people sleeping on the street in the downtown area had increased dramatically, and many were using drugs.

Some deported people use the programs that provide food to people on the street. A lot are homeless people, and families who live in Tijuana. On the border there is supposedly less extreme poverty, at least in the media coverage, but we meet families who get meals at the food distribution sites because they don’t have enough money to eat.

Rents here have increased a lot. Many of our students come from the south of the country and try to find housing here on the border in Tijuana with a modest scholarship. In the past they could live well with that scholarship. Now they can’t. They tell us the rents are very high, about $200 for a room and $500 for a two-bedroom apartment. Rent that high didn’t exist before.

Our rents are rising because of the real estate crisis in California, where the rents right across the border are much higher. Because of that, the number of people who cross to work in the United States has increased a lot. And because they can pay more, the rents here go up, and more people wind up on the street.

But there are also homeless people who choose to come to live in Tijuana. For a long time, we’ve seen a kind of reverse migration, crossing the border from north to south. Many homeless people in California come here to Mexico because here they can live with less. Many people who are threatened with deportation come to Tijuana because they can no longer pay the rents in California.

DB: What support are migrants in Tijuana receiving from the government now?

LV: Claudia Sheinbaum, our president, talks about her vision of supporting migrants through the consulates, with shelters, and reintegrating them by finding them employment. These are good goals, but they’re often not coordinated with the state and local governments. There’s a lot of disorganization, even though there are good intentions.

Sometimes, as we saw in one recent case, local governments can be a big obstacle. The director of the Migrant Institute here, José Luis Pérez Canchola, worked for the municipal and state administrations. Canchola has been a left political activist for many years and was a founder of MORENA [Movimiento de Regeneración Nacional, Mexico’s dominant political party]. He was fired, despite Sheinbaum’s vision. When Trump first came into office he went to the border crossing, where many foreign migrants had assembled, waiting for the border to open. They’d heard the United States was going to let them in, and of course instead it closed the border. There were many children and families in the street with nowhere to go, and Canchola tried to convince them to leave. The city government accused him of trying to pressure it and fired him.

Sometimes the consulates in the United States give people threatened with deportation help and legal advice, but once they’re here in Mexico they get much less attention. There is a program to give returnees a little money, a phone card, and a kind of ID. The ID is important for those who are deported, since without one there’s often a problem with the police. The government created one shelter here, but it wasn’t really necessary. There are a lot of shelters in Tijuana, so it was practically empty.

David Bacon is a writer and photographer, and former factory worker and union organizer. His latest book is More Than a Wall/Mas que un Muro (Colegio de la Frontera Norte, 2021).

Laura Velasco is an investigator and professor at Colegio de la Frontera Norte in Tijuana.

Note: Thanks to Laura Velasco and also Michelle Lerach and Yolanda Walther-Meade for their help.